Architecture Overview

Processing of RTP/RTCP packets

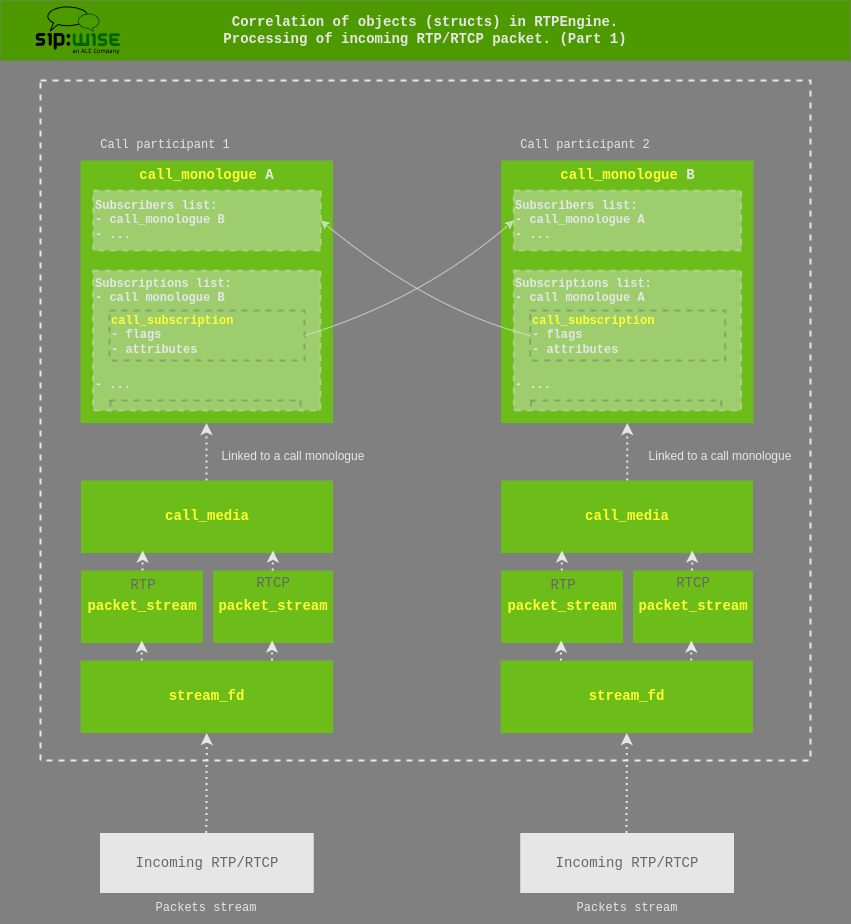

An incoming RTP is initially received by the stream_fd, which directly links it to the correlated packet_stream.

Each packet_stream then links to an upper-level call_media — generally there are two packet_stream objects per call_media, one for RTP and one for RTCP. The call_media then links to a call_monologue, which corresponds to a participant of the call.

The handling of packets is implemented in media_socket.c and always starts with the stream_packet().

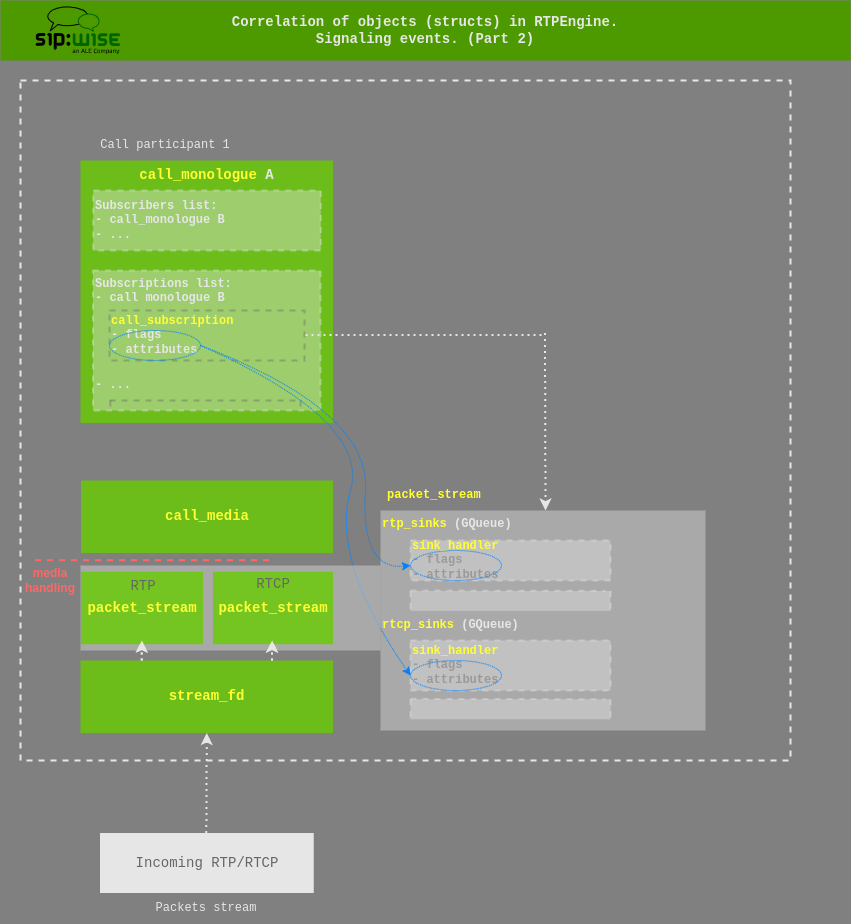

This operates on the originating stream_fd (fd which received the packet) and on its linked packet_stream and eventually proceeds to going through the list of sinks, either rtp_sinks or rtcp_sinks (egress handling) and uses the contained sink_handler objects, which points to the destination packet_stream, see:

stream_fd -> packet_stream -> list of sinks -> sink_handler -> dst packet_stream

To summarize, RTP/RTCP packet forwarding then consists of:

Determining whether to use

rtp_sinks orrtcp_sinksIterating this list, which is a list of

sink_handlerobjectsEach sink handler has an output

packet_streamand astreamhandlerCalling the stream handler’s input function to decrypt, if needed (but, a nuance)

Checking the RTP payload type and calling the codec handler, if there is one (e.g. for transcoding)

Calling the

streamhandler’s output function to encrypt, if neededSending the packet out to the output packet stream

Repeat

appendix 1

In practice the stream handler’s input function (step 4) is called only once, before going into the loop to send packets to their destinations.

The reason for that — there’s a duplication of input functions in the stream handlers, this is:

Legacy, because previously used to have a single output for each packet stream (and this part hasn’t been rewritten yet)

Theoretically it’s possible to save the effort of re-encrypting SRTP > SRTP forwarding, if some of the outputs are plain RTP, meanwhile other outputs are SRTP pass-through (but that part isn’t implemented).

As for setting up the kernel’s forwarding chain: It’s basically the same process of going through the list of sinks and building up the structures for the kernel module, with the sink handlers taking up the additional role of filling in the structures needed for decryption and encryption.

Other important notes:

Incoming packets (ingress handling):

sfd->socket.local: the local IP/port on which the packet arrived

sfd->stream->endpoint: adjusted/learned IP/port from where the packet was sent

sfd->stream->advertised_endpoint: the unadjusted IP/port from where the packet was sent. These are the values present in the SDP

Outgoing packets (egress handling):

sfd->stream->rtp_sink->endpoint: the destination IP/port

sfd->stream->selected_sfd->socket.local: the local source IP/port for the outgoing packet

Handling behind the NAT:

If rtpengine runs behind the NAT and local addresses are configured with different advertised endpoints,

the SDP would not contain the address from ...->socket.local, but rather from sfd->local_intf->spec->address.advertised (of type sockaddr_t).

The port will be the same.

Binding to sockets:

Sockets aren’t indiscriminately bound to INADDR_ANY (or rather in6addr_any),

but instead are always bound to their respective local interface address and with the correct address family.

Side effects of this are that in multi-homed environments, multiple sockets must be opened

(one per interface address and family), which must be taken into account when considering RLIMIT_NOFILE values.

As a benefit, this change allows rtpengine to utilize the full UDP port space per interface address, instead of just one port space per machine.

Marking the packet stream

The packet_stream itself (or the upper-level call_media) can be marked as:

SRTP endpoint

ICE endpoint

send/receive-only

This is done through the transport_protocol element and various bit flags.

Currently existing transport_protocols:

RTP AVP

RTP SAVP

RTP AVPF

RTP SAVPF

UDP TLS RTP SAVP

UDP TLS RTP SAVPF

UDPTL

RTP SAVP OSRTP

RTP SAVPF OSRTP

For more information about the RTP packets processing see RTP packets processing of the “Mutexes, locking, reference counting” section.

Call monologue and handling of call subscriptions

Each call_monologue (call participant) contains a list of subscribers and subscriptions,

which are other call_monologue’s. These lists are mutual.

A regular A/B call has two call_monologue objects with each subscribed to the other.

So that, one call_monologue = half of a dialog.

Subscribers of certain monologue — are other monologues, which will receive the media sent by the source monologue.

The list of subscriptions is a list of call_subscription objects which contain flags and attributes.

NOTE: Flags and attributes can be used, for example, to mark a subscription as an egress subscription.

On the diagram above you can clearly see how monologues and hence subscriptions are correlated.

A handling of call subscriptions is implemented in the call.c file.

In this regard, one of the most important functions here is __add_subscription().

A transfer of flags/attributes from the subscription (call_subscription) to the correlated sink handlers (sink_handler objects list) is done using the __init_streams() through the __add_sink_handler().

Signaling events

During signalling events (e.g. offer/answer handshake), the list of subscriptions for each call_monologue is used to create the list of rtp_sink and rtcp_sink sinks given in each packet_stream. Each entry in these lists is a sink_handler object, which again contains flags and attributes.

NOTE: ‘sink’ - is literally a sink, as in drain. Basically an output or destination for a media/packet stream.

During the execution, the function __update_init_subscribers() goes through the list of subscribers,

through each media section and each packet stream, and sets up the list of sinks for each packet stream, via __init_streams().

This populates the list of rtp_sinks and rtcp_sinks for each packet stream.

Flags and attributes from the call_subscription objects are copied into the according sink_handler object(s).

During actual packet handling and forwarding, only the sink_handler objects (and the packet_stream objects they related to) are used, not the call_subscription objects.

Processing of signaling event (offer/answer) to rtpengine,

in terms of using functionality looks as following (for one call_monologue):

signaling event begins (offer / answer)

monologue_offer_answer()->__get_endpoint_map()->stream_fd_new()in

stream_fd_new()we initialize a new poller item (poller_item),

and then using thestream_fd_readable(), thepi.readablemember is set:

pi.readable = stream_fd_readable;

in the

main.hheader, there is a globally defined poller, to which we add a newly initialized poller item, like this:

struct poller *p = rtpe_poller;

poller_add_item(p, &pi);

poller will be used to later destroy this reference-counted object

later, the

stream_fd_readable()in its turn, will trigger thestream_packet()for RTP/RTCP packets processingmonologue_offer_answer()now continues processing and callsupdate_init_subscribers()to go through the list of subscribers (through related to them media and each packet stream) and using__init_streams()sets up sinks for each stream.

Then, each sink_handler points to the correlated egress packet_stream and also to the streamhandler.

The streamhandler in its turn is responsible for handling an encryption, primarily based on the transport protocol used.

There’s a matrix (a simple lookup table) of possible stream handlers in media_socket.c, called __sh_matrix.

Stream handlers have an input component, which would do decryption, if needed, as well as an output component for encryption.

For more information regarding signaling events, see Signaling events, additional information of the “Mutexes, locking, reference counting” section.

Mutexes, locking, reference counting

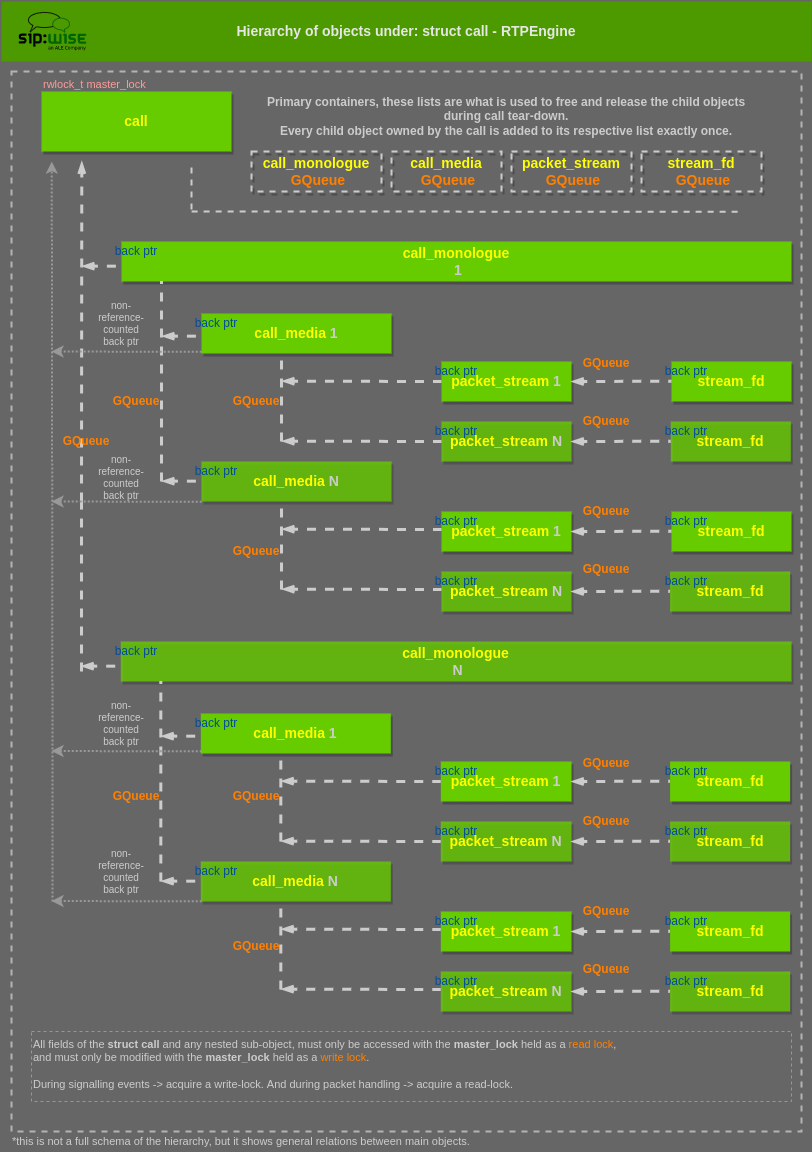

Struct call

The main parent structure of all call-related objects (packet streams, media sections, sockets and ports, codec handlers, etc) is the struct call. Almost all other structures and objects are nested underneath a call.

The call structure contains a master read-write lock: rwlock_t master_lock, that protects the entire call and all contained objects.

With the exception of a few read-only fields, all fields of call and any nested sub-object must only be accessed with the master_lock held as a read lock, and must only be modified with the master_lock held as a write lock.

The rule of thumb therefore is: during signalling events acquire a write-lock, and during packet handling acquire a read-lock.

Object/struct hierarchy and ownership

The logical object hierarchy is call → call_monologue → call_media → packet_stream → stream_fd.

Each parent object can contain multiple of the child objects (e.g. multiple call_media per call_monologue) and

each child object contains a back pointer to its parent object. Some objects contain additional back pointers for convenience, e.g. from call_media directly to call. These are not reference counted as the child objects are entirely owned by the call,

with the exception of stream_fd objects.

The parent call object contains one list (as GQueue) for each kind of child object.

These lists exist for convenience, but most importantly as primary containers. Every child object owned by the call is added to its respective list exactly once, and these lists are what is used to free and release the child objects during call teardown.

Additionally most child objects are given a unique numeric ID (unsigned int unique_id) and it’s the position in the call’s GQueue that determines the value of this ID (which is unique per call and starts at zero).

Reference-counted objects

Call objects are reference-counted through the struct obj contained in the call.

The struct obj member must always be the first member in a struct. Each obj is created with a cleanup handler (see obj_alloc()) and this handler is executed whenever the reference count drops to zero. References are acquired and released through obj_get() and obj_put() (plus some other wrapper functions).

The code bases uses the “entry point” approach for references, meaning that each entry point into the code (coming from an external trigger, such as a received command or packet) must hold a reference to some reference-counted object.

Signaling events additional information

The main entry point into call objects for signalling events is the call-ID:

therefore the main entry point is the global hash table rtpe_callhash (protected by rtpe_callhash_lock),

which uses call-IDs as keys and call objects as values, while holding a reference to each contained call. The function call_get() and its sibling functions perform the lookup of call via its call-ID and return a new reference to the call object (i.e. with the reference count increased by one).

Therefore the code must use obj_put() on the call after call_get() and after it’s done operating on the object.

RTP packets processing additional information

Another entry point into the code is RTP packets received on a media port. Media ports are contained in a struct stream_fd and because this is also an entry-point object, it is also reference counted (contains a struct obj).

NOTE: The object responsible for maintaining and holding the entry-point references is the poller.

Each stream_fd object also holds a reference to the call it belongs to

(which in turn holds references to all stream_fd objects it contains, which makes these circular references).

Therefore stream_fd objects are only released, when they’re removed from the poller and also removed from the call (and conversely, the call is only released when it has been dissociated from all stream_fd objects, which happens during call teardown).

Non-reference-counted objects

Other structs and objects nested underneath a call (e.g. call_media) are not reference counted as they’re not entry points into the code, and accordingly also don’t hold references to the call even though they contain pointers to it.

These are completely owned by the call and are therefore released when the call is destroyed.

Packet_stream mutex

Each packet_stream contains two additional mutexes (in_lock and out_lock).

These are only valid if the corresponding call’s master_lock is held at least as a read-lock.

The in_lock protects fields relevant to packet reception on that stream,

while the out_lock protects fields relevant to packet egress.

This allows packet handling on multiple ports and streams belonging to the same call to happen at the same time.

Kernel forwarding

The kernel forwarding of RTP/RTCP packets is handled in the xt_RTPENGINE.c / xt_RTPENGINE.h.

The linkage between user-space and kernel module is in the kernelize_one() (media_socket.c),

which populates the struct that is passed to the kernel module.

To be continued..

Call monologue and Tag concept

The concept of tags is taken directly from the SIP protocol.

Each call_monologue has a tag member, which can be empty or filled.

The tag value will taken:

for the caller - From-tag (so will be always filled)

for the callee - To-tag (but will be empty, until first reply with a given Tag is received)

Things are getting slightly more complicated, when there is a branched call.

In this situation, the same offer is sent to multiple receivers, possibly with different options.

At this point of time, multiple monologues are created in rtpengine and all of them without a known tag value

(essentially without To-tag).

At this point they all are distinguished by the via-branch value.

And when the answer comes through, the via-branch is used to match the monologue,

and then we assign the str tag value to this particular call_monologue.

In a simplified view of things, we have the following:

A (caller) = monologue A = From-tag (session initiation)

B (callee) = monologue B = To-tag (183 / 200OK)

NOTE: Nameless branches are branches (call_monologue objects) that were created from an offer but that haven’t seen an answer yet.

Once an answer is seen, the tag becomes known.

NOTE: From-tag and To-tag strictly correspond to the directionality of message, not to the actual SIP headers.

In other words, the From-tag corresponds to the monologue sending this particular message,

even if the tag is actually taken from the To header’s tag of the SIP message, as it would be in a 200 OK for example.

Flags and options parsing

Flags

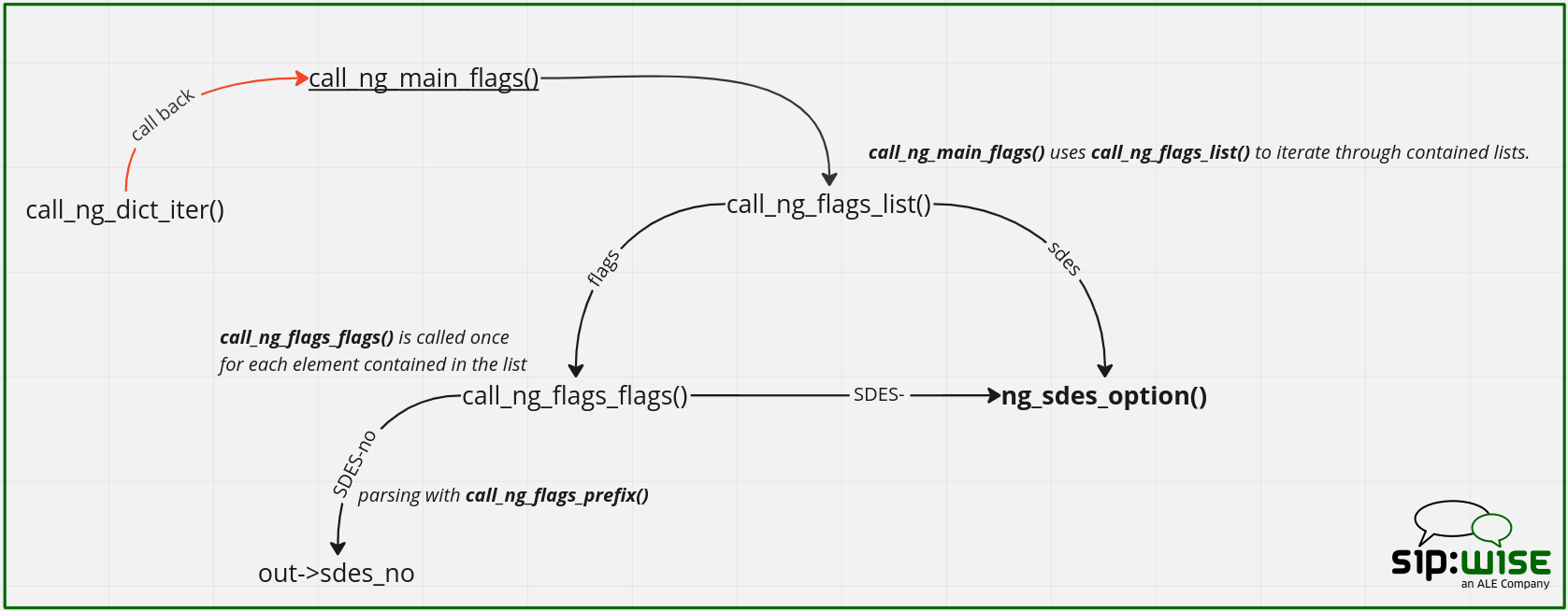

There are few helper functions to iterate the list of flags and they use callback functions.

The top-level one is call_ng_main_flags(), which is used as a callback from call_ng_dict_iter().

call_ng_main_flags() then uses the call_ng_flags_list() helper to iterate through the contained lists, and uses different callbacks depending on the entry.

For example, for the flags:[] entry, it uses call_ng_flags_list(), which means call_ng_flags_flags() is called once for each element contained in the list.

Let’s assume that the given flag is the SDES-no-NULL_HMAC_SHA1_32.

Consider the picture:

NOTE: Some of these callback functions have two uses. For example ng_sdes_option() is used as a callback for the "SDES":[] list (via the call_ng_flags_list()), and also for flags found in the "flags":[] list that starts with the "SDES-" prefix via call_ng_flags_prefix().